On 5th July 1948 the National Health Service was established in the United Kingdom. Britain was the first western country to offer free at the point of use medical care to the whole population.[1] Seventy-five years on the NHS continues to be a distinguishing feature of the British welfare state.

But how did the NHS come to be? Let us look back to the creation of the National Health Service and how the government of the day led by Prime Minister Clement Attlee set about introducing this transformative reform.

The Second World War led to an immense loss of life and induced considerable hardships. Britons endured rationing (which continued after the war was over), evacuation, destruction or damage to millions of homes and workplaces, air raids as well as the mass pivoting of the nation’s people and resources to meet the vast war effort. The period between the First and Second World Wars had also left its mark. The interwar years were a time of economic depression and social deprivation, there had been no great development of state provision. Attlee and his Cabinet had lived through (and in many cases fought in) both wars and recognised the need for reconstruction and expansion – a comprehensive welfare system was at the heart of this.

During the Second World War, the coalition government led by Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Leader of the Labour Party Clement Attlee (Deputy Prime Minister from 1942) seized on the need for post war reconstruction. Despite the preoccupation with fighting a world war, the government prioritised planning for this. In June 1941, Labour minister Arthur Greenwood announced to the House of Commons that a new committee had been formed to survey existing social security provision and allied services under the chairmanship of Sir William Beveridge.[2] This became the totemic 1942 Beveridge Report, which identified ‘Five Giants’ that needed to be tackled in order for Britain to succeed economically and socially. The five giants were Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. Influential economist and civil servant John Maynard Keynes was also consulted by Beveridge during the making of the report. At his suggestion Beveridge modified some recommendations, thus Keynes believed the plan to be broadly affordable.[3]

The report was published on 2nd December 1942 and immediately became a best-seller at home and abroad (costing 2 shillings).[4] Some 256,000 copies of the full report, 369,000 copies of an abridged version and 40,000 copies of an American edition were sold in twelve months.[5] The proposals received widespread support across the political spectrum. The recommendations of the Beveridge Report widened the scope set by Lloyd George’s National Insurance Act (1911). Beveridge offered a blueprint for a comprehensive welfare state. In the years after publication, the coalition government worked on plans for turning the recommendations into reality, including producing a White Paper. Full implementation was however not guaranteed. In March 1943, Churchill warned against imposing significant new expenditures without knowing the full post war economic picture; yet he also advocated a ‘national compulsory insurance for all classes for all purposes from the cradle to the grave.’[6]

On 5th July 1945 the Labour Party led by Clement Attlee won a landslide victory at the polls, with a majority of 146 seats.[7] After winning the General Election, the Attlee government set about creating a comprehensive welfare state, at the heart of which was the NHS. Indeed Labour had entered the election offering ‘the full Beveridge’.[8] Attlee’s ‘executive efficiency’ would be integral to introducing and implementing such a huge programme.[9] Though Britain and its allies had emerged victorious, the strain of total war had left the country in a desperate state. Yet Attlee reflected:

We had not been elected to try to patch up an old system but to make something new ... I therefore determined that we would go ahead as fast as possible with our programme.[10]

Attlee’s social and political work in the East End of London shaped his view of the role of the state. By the time he was in government, ideas that had seemed very much his own were now part of an emerging consensus. Attlee wrote, ‘I have witnessed now the acceptance by all leading politicians in this country and all the economists of any account of the conception of the utilisation of abundance.’[11] In 1918 as a soldier in the First World War Attlee expounded his sense of purpose, ‘We live in a state of society where the vast majority live stunted lives – we endeavour to give them a freer life.’[12]

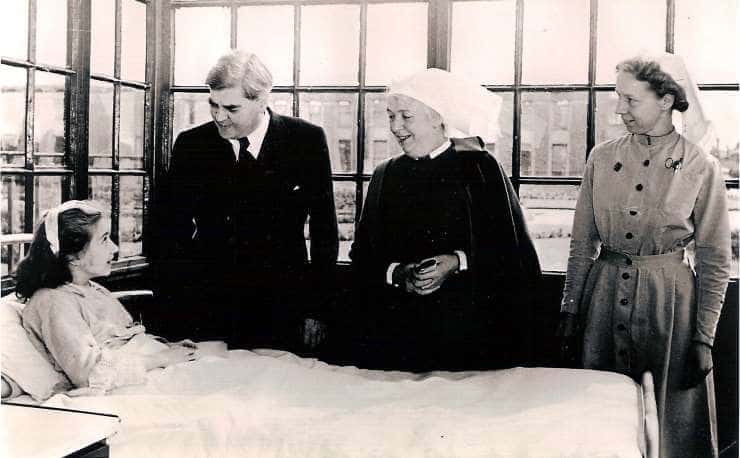

On arrival in Downing Street, Attlee faced a challenging economic picture. A month into office it got gloomier with the abrupt end of the US Lend-Lease scheme. Subsequently the US made a further loan agreement with Britain however Hugh Dalton, Attlee’s Chancellor of the Exchequer (1945-47) noted that the situation remained ‘desperately difficult’.[13] US Marshall Aid from 1948 until 1951 would also provide critical support for the British economy. Attlee, in assembling his Cabinet, appointed the political firebrand, South Wales miner and trade unionist Aneurin Bevan as Minister of Health. The King’s Speech on 15th August 1945 outlined an ambitious legislative programme including nationalisation of the fuel and power industries, civil aviation, Bank of England as well as establishing a National Health Service.[14] Chancellor Hugh Dalton worked closely with Bevan to establish the financial foundation for the introduction of the NHS. Dalton found Bevan’s vitality and drive impressive, and Bevan’s biographer credits Dalton as ‘after Bevan … the chief architect’ of the NHS.[15]

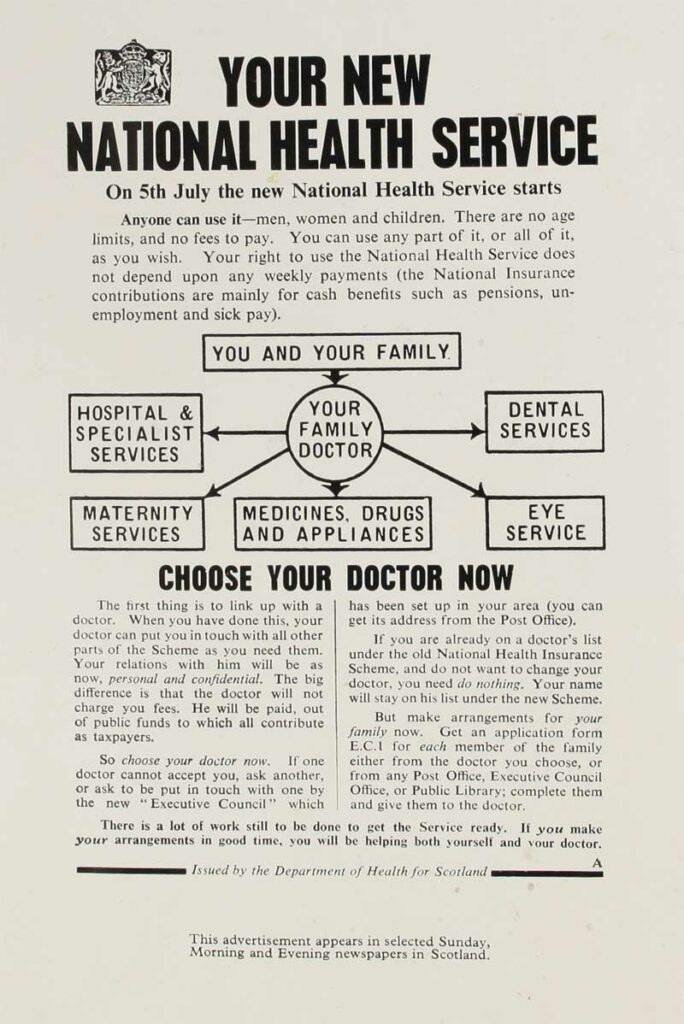

During the Second World War, the scope of health insurance had been extended but it covered just half of the population and did not include hospital and specialist services, dental, optical, or hearing services.[16] Universal provision regardless of ability to pay was at the core of the Attlee government’s new reforms. Minster of Health, Bevan set about building on the Beveridge Report and the coalition government’s White Paper. In October 1945, Bevan outlined his vision for a National Health Service. In December, he explained to Cabinet that this was ‘an opportunity, which may not recur for years, for a thorough overhaul and reconstruction of the country’s health position.’[17] Prime Minister Attlee drew on a cricket metaphor to express his approval, Bevan had done well “on a pretty sticky wicket”.[18] Provisions would include hospital care, ambulance services, GP services, maternity care, prescriptions as well as optical care and dentistry.[19]

Turning the NHS from principle to policy required significant structural change and thus extensive negotiations with the medical profession, local authorities, committees, Parliament and with other Cabinet ministers. It was an arduous process to say the least. What’s more, the NHS was one of a series of reforms which formed the welfare state. How the state would pay for these reforms was a huge matter for the government of the day. Keynes had told the War Cabinet in May 1945 that Britain faced a ‘financial Dunkirk’.[20] The 1946 National Insurance Act[21] extended the contributions of working age people (except married women) in order to contribute to funding the provisions of the welfare state.

Given its foundational status for the whole welfare programme, Attlee focused his attention on ensuring the passage of the National Insurance Bill. In the House of Commons during the first and second readings, Attlee reflected on the historical battle for social reform and credited earlier pioneers.[22] The Prime Minister also acknowledged the significant financial cost:

The question is asked – can we afford it? … Supposing the answer is “No”, what does that mean? It really means that the sum total of the goods produced and the services rendered by the people of this country is not sufficient to provide for all our people at all times, in sickness, in health, in youth and in age ... I cannot believe … that we can submit to the world that the masses of our people must be condemned to penury.[23]

The National Health Service Act received Royal Assent on 6th November 1946. This however marked the beginning of a deeper, more protracted phase of negotiations in the run up to so-called “Appointed Day” on 5th July 1948 – when NHS provision would begin. As such 1,143 voluntary hospitals (90,000 beds) and 1,545 municipal hospitals (390,000 beds) were taken over by the NHS in England and Wales.[24]

Historian Pauline Gregg recounted how nail-bitingly close it got:

Six months before the Appointed Day it looked as though the whole edifice might crash through lack of support from the medical profession; but a near-last-minute agreement saved the structure.[25]

Up to this point the medical profession exercised a significant degree of autonomy and so the creation of a National Health Service would lead to some loss of freedom as well as increased bureaucratic demands. Bevan recognised this and stated:

Any health service which hopes to win the consent of the doctors must allay these fears. … There is no alternative to self-government by the medical profession in all matters affecting the content of its academic life. … It is for the community to provide the apparatus of medicine for the doctor. It is for him to use it freely in accordance with the standards of his profession.[26]

The Minister of Health however was also determined to deliver his mission:

No society can legitimately call itself civilised if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means.[27]

Bevan secured the support of Cabinet to table a debate in the Commons on 9th February 1948, which confirmed the government’s determination to begin NHS provision on Appointed Day.[28] In the February debate, Bevan detailed the ‘wholesale resistance to the implementation’ the NHS Act from the professional bodies.[29] Over the proceeding months, Bevan made concessions and gave assurances to the medical profession on clinical freedom.[30] By Appointed Day, a majority of GPs had applied to enter the NHS and three quarters of the population had registered with the NHS.[31] As the river of NHS provision began to flow, Bevan turned to his Parliamentary Private Secretary Barbara Castle and said:

Barbara, if you want to know what all this is for, look in the perambulators [prams].[32]

Dr Michelle Clement is Lecturer and researcher on government reform and delivery at The Strand Group, King’s College London and Researcher in Residence at No.10 Downing Street. @MLClem @TheStrandGroup

[1] R. Klein, The New Politics of the NHS (Radcliffe Publishing, 2006), p.1.

[2] P. Gregg, The Welfare State (George G. Harrap & Co, 1967), p.18.

[3] J. Harris, William Beveridge: A Biography (OUP, 1977), p.412.

[4] P. Gregg, The Welfare State (George G. Harrap & Co, 1967), p.19.

[5] P. Gregg, The Welfare State (George G. Harrap & Co, 1967), p.19.

[6] M. Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill: Road to Victory 1941-45 (Heinemann, 1986), p.367.

[7] The first overall majority for the Labour Party.

[8] P. Hennessy, A Duty of Care: Britain Before and After Covid (Penguin, 2022), p.5.

[9] R. Burridge, Clement Attlee (Cape, 1985), p.204

[10] C. Attlee, As It Happened (Sharpe Books, 2019), p.165.

[11] J. Bew, Citizen Clem (Kindle edition, riverrun, 2016), p.578.

[12] J. Bew, Citizen Clem (Kindle edition, riverrun, 2016), p.579.

[13] H. Dalton, High Tide and After: Memoirs 1945-1960 (Muller, 1962), p.xi.

[14] The King’s Speech, Hansard, Vol. 137, 15 August 1945.

[15] B. Pimlott, Hugh Dalton (Papermac, 1986), p.495.

[16] P. Gregg, The Welfare State (George G. Harrap & Co, 1967), p.49.

[17] CAB/129/5 ‘Proposals for a National Health Service’, 13 December 1945, The National Archives,

http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-5-cp-45-339-39.pdf

[18] J. Bew, Citizen Clem (Kindle edition, riverrun, 2016), p.567.

[19] In 1951, under the Attlee government, charges for dentistry and optical care were introduced. The following year the Churchill government brought in prescription charges.

[20] P. Hennessy, A Duty of Care: Britain Before and After Covid (Penguin, 2022), p.7.

[21] Which built on the 1911 National Insurance Act.

[22] J. Bew, Citizen Clem (Kindle edition, riverrun, 2016), p.573.

[23] P. Hennessy, Never Again: Britain 1945-51 (Cape, 1992), p.119.

[24] G. Rivett, “1948-1957: Establishing the National Health Service”, Nuffield Trust, 2014,

https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/chapter/1948-1957-establishing-the-national-health-service

[25] P. Gregg, The Welfare State (George G. Harrap & Co, 1967), p.51.

[26] A. Bevan, In Place of Fear (Kindle edition, Lume Books, 2020), Loc 1605-1630.

[27] A. Bevan, In Place of Fear (Kindle edition, Lume Books, 2020), Loc 1353.

[28] K. Harris, Attlee (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1982), p.423.

[29] House of Commons ‘National Health Service’ Debate, 9 February 1948,

https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1948/feb/09/national-health-service

[30] R. Lowe, The Welfare State in Britain since 1945 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), p.179

[31] P. Gregg, The Welfare State (George G. Harrap & Co, 1967), pp.62-63.

[32] P. Hennessy, Distilling the Frenzy: Writing the History of One’s Own Times (Biteback, 2012), p.10.

1 comment

Comment by John posted on

Enlightening.